Jazz, like the sector it mirrored, was once in flux in 1969. That yr, Miles Davis launched In a Silent Means, an album whose low-key surroundings belied its standing as a usher in of main upheaval, main the tune right into a decade of electrical tools, studio-driven experiments, and rhythms that drew as a lot from funk and R&B as swing. But a number of other folks had been nonetheless enjoying adjustments in the old fashioned method: A musician may dedicate their whole existence to mastering the artwork, and simply because Miles was once all at once doing tape manipulation and taking note of Sly and the Circle of relatives Stone didn’t imply everybody else was once following go well with. And loose jazz, a decade or so outdated at that time, was once nonetheless an intensive pressure, its gildings and deconstructions of melody offering exchange routes ahead from custom, ones that didn’t essentially require plugging in in any respect.

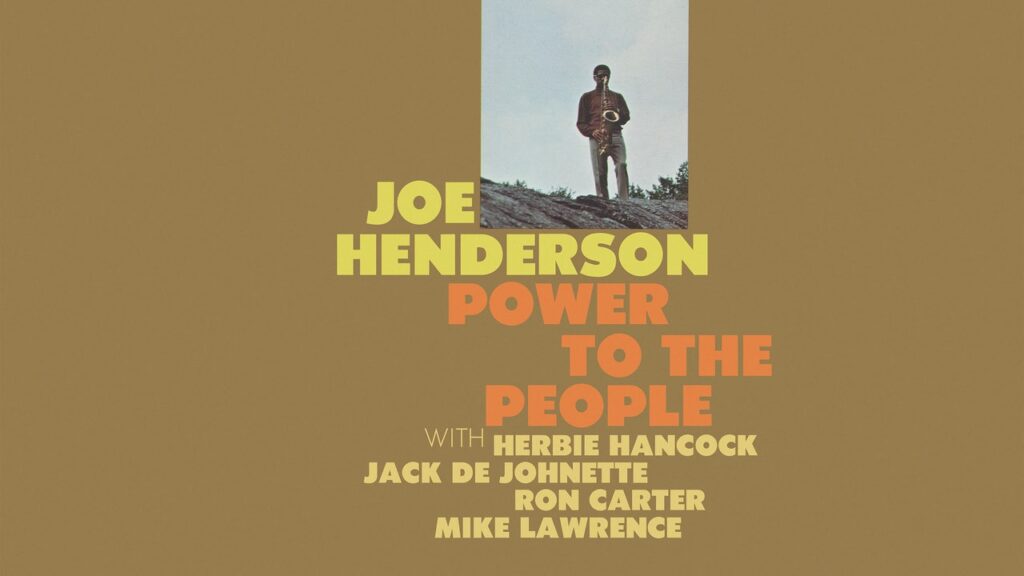

Taking a look again, it’s tempting to peer those quite a lot of types—fusion, straight-ahead, avant-garde—as totally distinct and walled off, and it’s true that positive gamers might be dogmatic of their adherence to at least one idiom and rejection of the others. The case of tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson offers excellent explanation why to believe them extra holistically. An old-school virtuoso who taught himself to play via transcribing and memorizing solos via bebop titans like Charlie Parker and Lester Younger, he additionally brushed the sides of loose jazz as a sideman with Andrew Hill, and inspired his personal supporting gamers to experiment with electronics even on data that instructed transparent of full-on fusion. His 1969 album Energy to the Folks, to be had on vinyl for the primary time in many years by means of a excellent new reissue from Craft Recordings and Jazz Dispensary, is an very important file of this transitional second, due partly to its author’s fail to remember for inflexible stylistic association. If you wish to pay attention, in one album, how jazz—it all—sounded simply prior to the flip of the ’70s, that you must do worse than this one.

Henderson surrounded himself with among the international’s easiest gamers for Energy to the Folks. Two, keyboardist Herbie Hancock and bassist Ron Carter, had been veterans of Davis’ band, and one, drummer Jack DeJohnette, was once simply becoming a member of up with Miles at round the similar time; Henderson additionally recruited up-and-coming trumpeter Mike Lawrence on two of the seven tracks. Around the album, Hancock switches between acoustic piano and Fender Rhodes, and Carter between upright and electrical bass, alternatives that replicate the album’s fluid stylistic manner. Carter’s collection of bass, specifically, is a coarse indicator of the place a given observe will fall at the spectrum. On upright, his number one software, he has a tendency towards conventional strolling strains, outlining the chords with a gentle pulse that the remainder of the gamers are loose to improvise round. On electrical, he dances extra freely across the outskirts of the pocket, jabbing out and in searching for new rhythmic chances, nudging the tune clear of the jazz’s well-worn solo-and-accompaniment layout and towards extra open-ended team improvisation.